I'm experiencing memory loss and declining mental abilities. Can I still prepare a standard representation agreement?

Some of us need support to make everyday decisions. This might be because of age-related cognitive decline. Or an intellectual disability. Or an unfortunate accident. With a standard representation agreement, you can legally authorize someone to help you make certain decisions. Learn about how these agreements can be used and how to prepare one.

What you should know

“I have an intellectual disability. There are many things I can do for myself. I enjoy spending time with friends. On Tuesdays and Wednesdays, I work at the library. I need Mom’s help a lot, so I asked her to be my representative. When I need to do anything at the bank, we go together. Tony is the bank manager. We’ve known him a long time. He talks to me about what I’d like to do with my money, but knows I’ve asked Mom to give me extra support.”

– Ella, Delta, BC

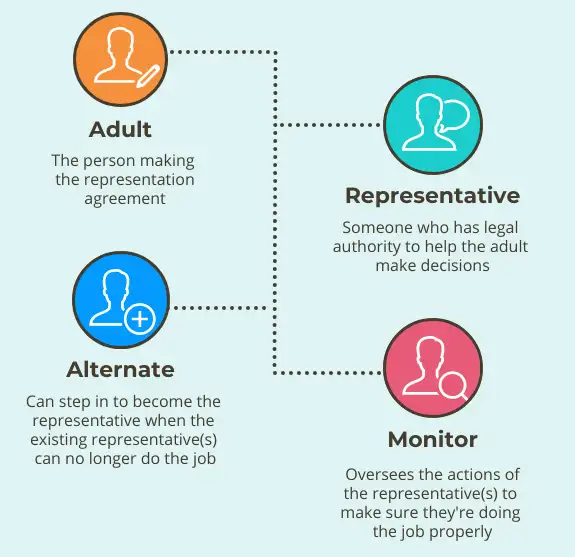

With a standard representation agreement, you can give someone the authority to help you make certain decisions. It's usually made by people who need support to make decisions now, and into the future.

This type of agreement is sometimes called a section 7 representation agreement, based on this underlying law. The relationship it establishes must be respected by outside parties. The agreement tells others that your representative is authorized by the law to help you do certain things. Banks, doctors and other service providers may insist on seeing the agreement before they talk to your representative.

Dealing with banks

Representatives may find that some banks will question their authority. Anecdotally, these kinds of agreements are most readily accepted when there’s a strong relationship between the family and the financial institution.

You might want to talk to your bank and service providers, with your representative, before you prepare a representation agreement. If they’re hesitant, you can remind them that there are specific laws that make these valid legal documents in BC. In this way, they’re no different from powers of attorney.

“I have a client, Marta, who is in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. She can still make simple choices like what to eat for lunch. But basic arithmetic confuses her. When her doctor explains medical procedures, she can’t understand. Marta is no longer capable of signing an enhanced representation agreement. But in my opinion, she can sign a standard representation agreement. She can choose someone she trusts to help her make decisions.”

– Oli, notary public, Surrey, BC

Standard representation agreements can only be made by adults (aged 19 years or older). A standard representation agreement may be appropriate for an adult:

with an intellectual disability

who suffered from a traumatic brain injury

experiencing age-related mental decline

whose cognitive function is otherwise impaired due to illness or accident

The relevance of “capability”

If you want to sign a legal document, the law usually requires you to be capable of understanding the nature and consequences of what you’re agreeing to. Say you wanted to sign a contract to buy a home. If you couldn’t comprehend that a home is worth a lot of money, the sale couldn’t go through.

The law sets a different standard of capability for making a standard representation agreement. It recognizes that everyone, including people with cognitive difficulties, have a right to meaningfully participate and direct their own lives. Under the law, an adult may make a standard representation agreement even if they’re not capable of either:

managing their own affairs (such as health care or routine finances), or

making a contract, as in the above example.

The law doesn’t outline a specific test of capability. All relevant factors need to be considered. For example, whether the adult:

communicates that they want their representative to help them make decisions

demonstrates choices and preferences

expresses feelings of approval or disapproval of others

is aware that the representative may make choices that affect them

has a relationship of trust with their representative

A diagnosis is not decisive

Capability shouldn’t be based solely on a diagnosis or IQ. And the law says it cannot be based on the way someone communicates.

“My sister Janis needs help to get on with everyday life. The people who are close to her have always helped her to make decisions. Janis formalized her support arrangement by signing a standard representation agreement. Her representatives all care deeply for her. Sometimes we get together as a group to talk with Janis about her decisions.”

– Carly, New Westminster, BC

You can choose anyone to be your representative, as long as they’re 19 years of age or older. Often, a representative is already highly involved in the life of the adult. It’s often a family member or friend.

A representative cannot be:

a paid caregiver, or

an employee at a facility where you live if the facility provides personal or health care services.

These restrictions don’t apply if the person providing the care or employed at the facility is your child, parent, or spouse.

You can choose more than one representative

You may already have certain people you turn to for help. Under a representation agreement, you can choose:

Different people to make different kinds of decisions. Sam can make financial decisions and Jo can make health care decisions.

Two or more people to make the same kind of decision. Sam, Jo and Ron can make financial decisions together. The document might say:

They must make decisions unanimously (the three of them must agree). Decisions must be made unanimously, unless the agreement says otherwise.

They can make decisions by consensus. Sam and Jo agree. Ron disagrees. If Ron can voice his displeasure but agree not to stand in the way of Sam and Jo, there’s still a consensus to proceed.

Each representative can make decisions independently.

The majority rules. Sam and Ron agree, Jo does not. The decision goes Sam and Ron’s way.

“Our son Phil had a ski accident. His head hit a rock — hard. We’ve been caring for him since, but know we won’t live forever. Phil chose his brother Marvin as his alternate representative. Marvin knows how Phil communicates, he knows his likes and dislikes, and he knows how to make him laugh! Phil can continue getting the support he needs after we’re gone.”

– Etta, Burnaby, BC

It’s wise to appoint an alternate representative. This is someone who can step in if your first choice can no longer act.

You aren't always required to, but it's always a good idea to appoint a monitor. A monitor’s job is to keep an eye on the representative. Nidus has a helpful fact sheet on the role of a monitor.

Situations where you must appoint a monitor

Where a representative is authorized to help you with your routine finances, you must appoint a monitor, unless:

there are two or more representatives who act unanimously to make financial decisions, or

the representative is your spouse, the Public Guardian and Trustee, a trust company, or a credit union.

The representative's powers

Under a standard representation agreement, you can give someone power to make decisions in four areas:

Health care. Big and small health care decisions are covered. Minor health care includes routine tests, dental and eye work and medication. Major health care includes major surgery, chemotherapy, dialysis, complex diagnostic tests, and risky treatments.

Personal care. Includes diet, dress, social activities, exercise, where you’ll live and work, spiritual matters, and who you spend time with.

Routine management of financial affairs. Includes paying bills, banking, applying for benefits, paying taxes, paying off loans, and applying for insurance. Your representative can’t do anything beyond the routine. For example, more complex decisions such as selling or buying a home, or taking out a loan, are not covered.

Legal matters. Includes dealing with legal issues, getting legal advice and services, instructing a lawyer, and commencing any legal proceedings (except divorce proceedings).

You cannot authorize your representative to:

Physically restrain, move, or manage you, against your will.

Help make a decision to refuse health care that’s necessary to preserve your life. This means some end-of-life decisions are off the table. But your representative could still, say, consent to medication to ease your pain at end-of-life.

The representative’s duties

A representative has certain legal duties. For example, they’re obliged to act honestly and in good faith. They must also act within the authority granted to them by the representation agreement.

The law provides a decision-making framework that a representative must follow. When helping you to make decisions, or making decisions for you, they must (in this order):

Consult with you to determine your current wishes and comply with your wishes, if it’s reasonable to do so.

Comply with instructions or wishes you expressed while capable. This step may not apply if you made an agreement when you had limited capacity. However, it may apply to you if you have fluctuating mental capacity.

If your wishes are not known, act based on your known beliefs and values.

If your beliefs, values and wishes are not known, act in your best interests.

With standard representation agreements, the law recognizes that everyone has the right to meaningfully participate in decisions that impact them. This includes anyone who is experiencing mental decline due to an accident or illness, and those with an intellectual disability. This is where supported decision-making comes in. It’s not about taking over and making decisions for someone. It’s about helping them find their way to their own solutions.

While supported decision-making is ideal, it might not always be appropriate or possible. It may not be a good fit for those:

who don’t have anyone close to them in their life

with fluctuating cognitive abilities

in the later stages of dementia, or another degenerative disease

For example, an adult’s condition may deteriorate after they’ve made a representation agreement. They may truly lose the capacity to make decisions of any sort. If this happens, a representative’s authority continues. At this point, it may be impossible to consult with the adult. The representative would need to take over decision-making for the adult.

What the law requires

The law says that when helping an adult to make a decision, a representative must consult with them about their wishes, and comply if it’s reasonable to do so. Even if it’s not reasonable to consult with an adult about their current wishes (what they want), a representative is required, by law, to make decisions that align with the adult’s known beliefs and values (what’s important to them).

There are different ways a standard representation agreement can end:

You, the person making the agreement, die.

A committee is appointed to make decisions for you.

The representative is your spouse and your relationship ends (unless the agreement says otherwise).

The representative dies or becomes mentally incapable (unless there’s another representative or an alternate representative).

You revoke — that is, end — the agreement. You need to do this at a time when you’d still be capable of making such an agreement.

Learn more about how to end a standard representation agreement.

Prepare a standard representation agreement

The starting point: every adult is presumed to be capable of making a standard representation agreement. This means any adult can make an agreement unless it’s demonstrated that they are not capable of doing so.

There’s no specific test of legal capability. Re-visit our discussion above on capability under “who can make a standard representation agreement.” It lists some of the relevant factors that should be considered.

Many adults have existing circles of support — certain people they turn to for help. Often, parents and other family members act as caregivers for their loved ones.

Think about what you’re asking your representative to do and who’s the best fit for the job. The decision may be intuitive. Or you may need support to make the decision. Remember, it is your choice.

Key considerations

Important things to consider when choosing a representative include:

Trust and familiarity. Is there an existing relationship of trust between you and your representative(s)? Are they familiar with how you communicate?

Loyalty. Choose someone who will make sure your needs and wishes — not theirs — come first. Your values, beliefs and wishes might be different from your family’s. Under the law, a representative must respect your right to make your own decisions, to the extent reasonable.

Willingness. Your representative should be interested and involved. Adults typically choose representatives who are highly engaged in their life. For example, do they understand your medical, mental health, and personal care needs?

Ability. Are they able to communicate clearly? Could they make difficult decisions in stressful situations?

Consider appointing an alternate representative

If you only name one representative, consider naming an alternate representative. An alternate can take over if something happens to the first representative. The agreement needs to clearly describe the circumstances when an alternate can step in.

You can ask a notary public or a lawyer to prepare your agreement — but you don’t have to.

If you decide to see a lawyer or notary public, find out how much they’ll charge. Phone around and compare prices. See the options for free or low-cost legal help.

Forms available online

A standard representation agreement form is available online through the BC government. You don’t have to use it, but the form gives you an idea of how to make this type of agreement.

Nidus Personal Planning Resource Centre & Registry provides basic forms and custom forms for what they call an RA7 (a section 7 representation agreement, another term for a standard representation agreement).

For a standard representation agreement to be effective, it has to be signed and witnessed properly.

Your signature must be witnessed

You must sign and date the agreement in front of two witnesses. The witnesses must also sign and date the agreement in front of you. One witness is sufficient if they are a notary public or a lawyer.

Witnessing can now be done electronically. That is, you can sign in each others’ electronic presence. There are a few requirements for electronic witnessing to be valid:

The witness must be a notary or a lawyer.

You must use audiovisual communication technology (such as Zoom or Facetime) that allows you to hear and see each other.

You must be able to communicate simultaneously, in a way that is similar to communication that would occur if you were physically present together.

You must sign and date complete and identical paper copies of the representation agreement.

You must include a statement that it was signed and dated in accordance with the alternative process provided in the Representation Agreement Regulation.

If someone is signing the representation agreement on your behalf, you must be in each other’s physical presence when they sign the representation agreement. The lawyer or notary witness may be in the electronic presence of you and the person signing on your behalf.

Here’s an example of what electronic witnessing might look like:

You and a notary or lawyer connect on a video call.

Each of you has an identical paper copy of the representation agreement.

You adjust your cameras to ensure that you can both see each other’s face at the same time as seeing each other sign the representation agreement.

The lawyer or notary watches you sign and date the representation agreement.

You watch the lawyer or notary sign the representation agreement.

After signing, you and the lawyer or notary discuss your plan to bring the signed representation agreement pages together to form the complete document. For example, you can mail or courier your originally signed page to the lawyer or notary. They can then put it together with their original signed witness page, along with the rest of the representation agreement.

Who can be a witness

A person can’t witness a signature if they are:

a representative,

an alternate representative,

a spouse, child, or parent of a representative or alternate, or

employed by a representative, unless they’re a lawyer, notary public, or the Public Guardian and Trustee.

The representative must sign the agreement

The representative (including any alternates) must sign the standard representation agreement. If there’s more than one representative, each must sign the document before they can act. But the representatives don’t all have to sign at the same time. And their signatures don’t need to be witnessed.

Other forms may be needed

There are other forms that may need to be signed for the agreement to be valid. These forms must be kept with the representation agreement. Versions of these forms are available here:

Representative or alternate representatives. The representative, and any named alternate representative must sign this form.

Witnesses. Each witness must sign this form.

If you have a monitor. If you have a monitor, they must sign this form. Re-visit our discussion above on monitors to decide whether you want or need to have one.

If an adult wants to be represented but is physically unable to sign the agreement. Someone else can sign on an adult’s behalf. This person can’t be a witness, a representative, or an alternate. The person signing on behalf of the adult must sign the representation agreement and this form. Their signature on the agreement and form must be witnessed. The adult who wants to be represented must be present at the signing, and direct the agreement to be signed.

One more detail

Except for the fourth form, each person who signs one of these forms must confirm that they’ve read certain sections of the Representation Agreement Act. You'll find the relevant sections referenced in each form. View a current version of this Act on CanLII.

Your agreement will be most effective if your representative knows what you like, don’t like, and want. So once you’ve both signed the agreement, sit down and talk to them! Your representative is there to help your voice be heard.

If you’re experiencing a decline in memory or cognition, it’s best to have that conversation early on. Knowing your goals and values will better prepare your representative to make decisions for you in the future.

Further supports for you and your representative

Nidus offers a fact sheet with tips for strengthening a standard representation agreement.

Community Living BC has developed a guide for adults with developmental disabilities. It’s not specifically about representation agreements, but it’s a guide for adults to lead their own decision-making process and develop a person-centred plan.

The agreement can be registered with the Nidus Personal Planning Registry. This is a registry for storing representation agreements and other documents.

Registering the document will act as a safeguard. You can permit trusted institutions and individuals to access your registered documents. For example, quick access to documents may be needed in emergency situations.

Common questions

Yes. You can choose to prepare a standard representation agreement even if you’re capable of making your own decisions independently. While there are other planning options available to you, you might still feel that a standard representation agreement is a good fit. Learn more about the differences between the two types of representation agreements.

Mental capability shouldn’t be based solely on a diagnosis. Your doctor’s medical opinion may be that you are mentally incapable. But the legal standard, in this context, is more flexible. Even if you can’t make decisions independently or manage your own affairs, under the law you may still make a standard representation agreement. For more, see the discussion above of who can make a standard representation agreement, under what you should know.

If it’s truly impossible for someone to express or indicate a choice or preference, in any way, that person would not be able to make a standard representation agreement. For example, someone in a coma would not be sufficiently aware of the world around them.

Remember, “communication” doesn’t just mean talking! Some people may have different ways of expressing themselves.

No. Legally, you can’t be required to enter into a representation agreement as a condition of receiving any good or service.

There’s a hierarchy of authority a health care provider must follow if a health care decision needs to be made. The first person who must be consulted is you. If you’re not capable of providing consent, there are other people the health care provider must seek consent from. Learn more about who the law says can make decisions for you in why someone might want to prepare a standard representation agreement.

Who can help

Alzheimer Society of BC

Support for British Columbians with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

Nidus Personal Planning Resource Centre & Registry

Detailed information on personal planning, including template forms.

Plan Institute

Helps people with disabilities and those who support them plan for the future.